Satellites are emerging as a tool to fight climate change, exposing hidden sources of greenhouse gas emissions and allowing governments to monitor compliance with international pacts.

Over the past three years, satellite images have been used to spotlight previously unreported leaks of methane—or to bump up estimates of known emissions—in Russia, Turkmenistan, Texas’ Permian Basin and elsewhere, in some cases triggering international scuffles.

The disclosures have come from private companies, environmental watchdogs and others, some working with data from multipurpose, space-agency-owned satellites. Governments, private companies and environmental groups are also launching dozens of specialized satellites focused solely on scouring the planet for greenhouse gases.

Beyond their use in communications and weather monitoring, satellites have long been a tool to hold adversaries accountable over national security, tracking troop buildups or weapons movements. Their role in monitoring emissions gives nations a new way to use the technology to point fingers at each other.

Several countries have expressed discomfort with satellite imagery potentially becoming fodder for a rival to “name and shame” them for emissions. China, in particular, has made clear it wants to control monitoring within its own borders and considers such satellites a national security issue, said

Stephane Germain,

chief executive of the Canadian satellite company GHGSat Inc., which monitors emissions.

“The overarching concern is they’re being monitored from space,” Mr. Germain said.

But multinational businesses already use satellites to track everything from Chinese steel production to shopper traffic at suburban American malls, and major oil companies support satellite monitoring as a way to show their compliance with clean-air standards. Big players including Saudi Aramco and

Exxon Mobil Corp.

are investors in GHGSat through the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, an industry consortium.

“‘It’s going to provide leakers with very few places to hide.’”

A key focus for climate-monitoring satellites is methane, a potent greenhouse gas that leaks erratically from wellheads, pipelines and storage tanks, making it tougher to detect—especially in remote locations and authoritarian countries that don’t allow field inspections or aircraft overflights.

“It’s going to provide leakers with very few places to hide,” said

Tim Gould,

chief energy economist at the Paris-based International Energy Agency, of satellite monitoring.

At the international climate summit in Glasgow next month, the U.S. and others—including the United Nations, private companies and the European Space Agency—will be among those advocating wider use of satellites for measuring progress toward cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

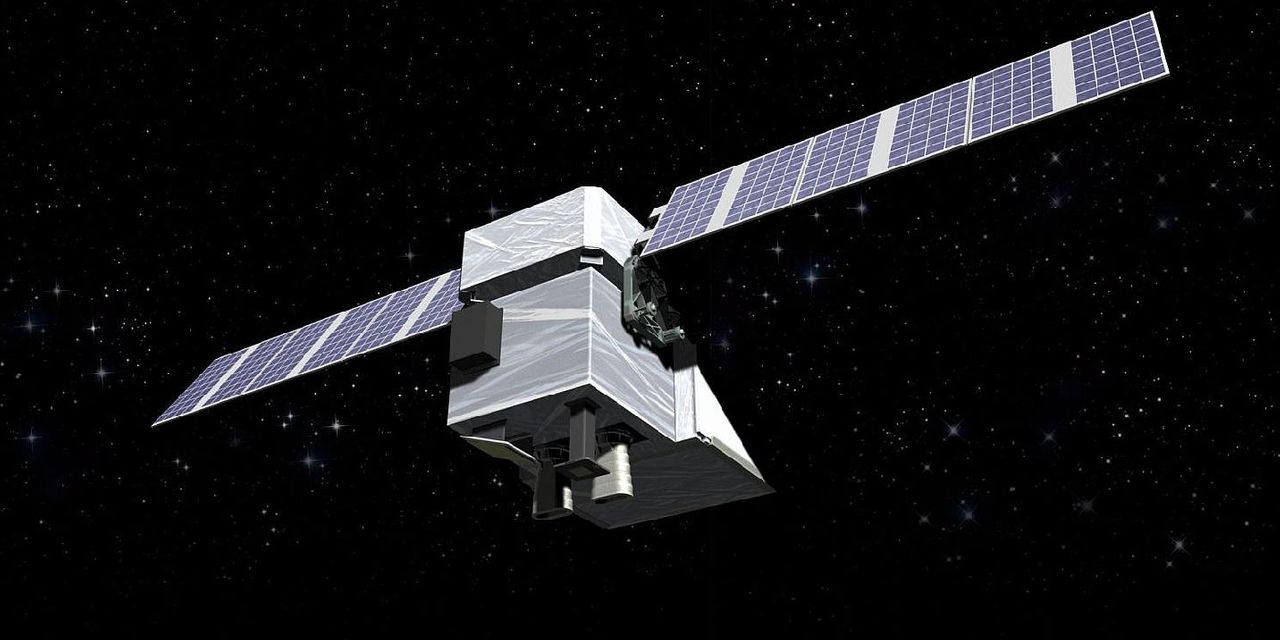

A digital rendering of MethaneSAT, an $88 million satellite project that the U.S.-based Environmental Defense Fund is building with support from the government of New Zealand and others.

Photo:

Ball Aerospace/MethaneSAT

Countries have struggled to meet targets they set for reducing emissions under the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement, which had no enforcement provisions for those that failed to meet their goals.

U.S. climate envoy

John Kerry

has said satellites can be useful in monitoring pollution from China, the world’s top greenhouse-gas emitter and whose government restricts information. Mr. Kerry signed a joint statement in July saying the U.S. would work with Russia to track emissions by satellite. Russia is the world’s top source of methane emissions from the oil-and-gas industry and the U.S. is No. 2, according to the IEA.

The advent of satellite technology hasn’t been without controversy. After the analytics company Kayrros claimed a big increase in methane emissions from Russia, using open-source data from European Space Agency satellites, Russian President

Vladimir Putin

dismissed criticism over the gas and said his country would launch its own satellites.

Beijing has said it is working to verify climate data from the rest of the world. It launched TanSat, also known as CarbonSat, in 2016 to monitor carbon emissions and plans to launch several more emissions-monitoring satellites through 2025, according to state media.

The French national space agency, the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales, or CNES, is working on a satellite-based climate monitoring project with the U.K., called Microcarb.

“Satellites are the best tool,” said CNES science chief

Juliette Lambin.

“They cover all the world in a few days.”

In the U.S., several public-private partnerships are building emissions-monitoring satellites. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Jet Propulsion Lab is providing the primary sensor for one of them, Carbon Mapper, a venture that includes partnerships with the state of California and clean-energy and climate-change think tank RMI.

A jet was prepared for a MethaneSAT test flight at a hangar in Broomfield, Colo., in July. The satellite project aims to help pinpoint how much methane is in the air and where gas leaks are occurring.

Scientist Jonathan Franklin set up a xenon emission lamp to calibrate a spectrometer built for detecting methane emissions.

Technicians worked on a Gulfstream jet owned by the U.S. National Science Foundation ahead of a flight to test the methane-monitoring technology.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

What role, if any, should satellite data play in regulating greenhouse-gas emissions? Join the conversation below.

At an airplane hangar in Broomfield, Colo., this summer, scientists from the Environmental Defense Fund, Harvard University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory gathered to work on a $88 million satellite project called MethaneSAT. The U.S.-based EDF is building the device with support from the government of New Zealand and others. Set to launch about a year from now, the satellite would be focused on detecting methane emissions globally.

“Russia’s not going to let you overfly their oil field with an airplane. The Middle East—it’s not going to happen,” said

Tom Ingersoll,

a venture-capitalist fund manager and co-leader of MethaneSAT. “With a satellite, it’s difficult to hide.”

The project is designed to detect methane using a spectrometer, which measures the reflection of sunlight off the Earth’s surface. Every chemical reflects light differently, and MethaneSAT’s sensor is built to target methane’s refractions.

For testing, the scientists put a spectrometer in a Gulfstream jet owned by the U.S. National Science Foundation, which provided funding for the project. The team aimed the spectrometer out of two peach-tinted portholes in the belly of the fuselage. From 45,000 feet over Texas, it was able to detect methane being released from a truck.

The device also caught something else: a large, unexpected methane plume nearby, which the system later revealed to be an unlit flare at an oil well pad.

“Seeing this plume, that’s the moment I knew this is working,” said

Jonathan Franklin,

a Harvard researcher who is overseeing the calibration of MethaneSAT’s spectrometer.

Once in space, the system will beam data to cloud-computing systems on Earth where algorithms interpret how much methane is in the air and where gas leaks are located.

Oil industry executives and their trade group, the American Petroleum Institute, say they welcome independent satellite-monitoring projects. They are also funding their own efforts, saying that the U.S. industry is a cleaner producer and that satellite data would back that up. In 2020 the U.S. produced 4.7% less in methane emissions than Russia despite producing 34% more oil and gas, according to IEA data.

The industry owns about a third of GHGSat, whose clients include

Royal Dutch Shell

PLC and

Chevron Corp.

MethaneSAT scientists Jenna Samra and Jonathan Franklin carried a spectrometer for the project’s satellite.

“Imagine a highly sensitive, accurate satellite that could verify those [methane] emissions and hold all exporting countries to the same standard,” Shell U.S. President

Gretchen Watkins

said. “That’s a win.”

GHGSat launched two satellites in the past year with resolution fine enough to zoom in on any of the millions of pipelines and wellheads world-wide. It plans to build up to 10 more with $45 million from a second round of fundraising finished in July.

The company drew attention in 2019 when it inadvertently discovered that human-made emissions might be making Turkmenistan one of world’s top methane emitters. GHGSat’s first satellite, “Claire,” which launched in 2016, was scanning for mud volcanoes when it discovered a faulty natural-gas compressor station instead.

A diplomatic effort pushed Turkmenistan to stop those emissions. But other leaks there persist—from pipelines, tanks and flares that are venting raw methane into the air rather than burning, according to GHGSat, which says such leaks are on pace this year to equal the emissions of nearly 10 million cars.

Russia has drawn similar attention. Kayrros, using data from existing European satellites, calculated in April that Russia had a 40% increase last year in methane plumes observed from pipelines and other gas infrastructure. Two months later, Kayrros cited satellite evidence to declare that in 2019 a pipeline in Russia’s Tatarstan was the likely source of the third-worst emissions burst it had ever found.

Write to Timothy Puko at tim.puko@wsj.com

Copyright ©2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8