Everyone knows the scene — James Watson and Francis Crick, discoverers of the DNA double helix, stroll right into a pub in Cambridge and declare, “We have now found the key of life!” The remaining is Nobel Prize historical past.

Besides, “[t]he most well-known scientific announcement of the 20 th century was not made in exactly the way in which most of us had been taught in highschool,” writes Dr. Howard Markel, director of the Middle for the Historical past of Drugs on the College of Michigan and PBS NewsHour columnist. “This apocryphal second, like so many others constituting the epic seek for DNA’s construction, has lengthy been exaggerated, altered, formed, and embellished.”

In his new ebook, “The Secret of Life: Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, Francis Crick, and the Discovery of DNA’s Double Helix,” Markel tells the way more sophisticated story, and what he calls one of the egregious rip-offs within the historical past of science.

“If life was honest, which it’s not, it will be known as the Watson-Crick-Franklin mannequin,” Markel advised the PBS NewsHour’s William Brangham in a dialog in September. Franklin was a British chemist whose X-ray diffraction picture of DNA was vital to Watson fixing the double helix thriller. However she was not credited and died at 37 earlier than the file may very well be corrected.

WATCH: Why discovery of DNA’s double helix was primarily based on ‘rip-off’ of feminine scientist’s information

So who was Franklin? She displayed extraordinary intelligence, sensitivity and spirit from a younger age, in response to accounts. Markel paints a vivid portrait of her as fiercely clever — and, often, merely fierce (Markel recounts how she as soon as acquired right into a scuffle over a Tesla coil that didn’t belong to her). In two excerpts from his ebook, we study her early attraction to science and incapacity to undergo fools, in addition to her time in France the place she blossomed as a younger researcher.

“Like many gifted younger folks, Rosalind Franklin erroneously assumed that her intense mental focus and fast, logical thoughts had been common and customary,” Markel writes. “All through her life, she had a tough time tolerating the mediocrity of others, typically on the expense of her skilled improvement.”

Beneath, learn extra by Markel about one of many hidden figures who helped advance the research of life as we all know it.

Excerpts from “The Secret of Life,” Chapter 6

By Howard Markel

As slightly lady, Rosalind distinguished herself from her siblings (one older brother, David; two youthful brothers, Colin and Roland; and a youthful sister, Jenifer) by being quiet of voice, observant of these round her, and perceptive in her judgments. Overly delicate, particularly if she felt slighted or wronged, her response as a teen was to retreat and ruminate. Her mom, Muriel, the very mannequin of the standard Jewish spouse, wrote greater than a decade after her second youngster’s dying, “When Rosalind was upset she would figuratively curl up—like touching the fronds of a sea anemone. She hid her wounds and bother made her withdrawn and upset. As a schoolgirl I at all times knew when one thing had gone improper at school by her silences when she acquired residence.”

Such sensitivity typically obscured her deeper abilities. In 1926, Rosalind’s aunt Mamie described to her husband a go to together with her brother and his household on the Cornwall coast. She supplied an exquisite characterization of the six-year-old Rosalind: “[she] is alarmingly intelligent—she spends all her time doing arithmetic for pleasure, & invariably will get her sums proper.” Equally apt was Muriel’s recollection of younger Rosalind’s “immensely glowing character, very sturdy and sensible—not simply mental brilliance, however a brilliance of spirit.” Maybe we ought to provide the final phrase to the eleven-year-old Rosalind, quickly after her mom launched her to the science behind growing images: “It makes me really feel all squidgy inside.”

“All her life Rosalind knew precisely the place she was going,” Muriel insisted; “her views had been decided and clear minimize.” As a youngster, Rosalind had already developed a pointy tongue and pointier elbows. She was unafraid of expressing her distaste or critique of others, particularly in the reason for science. To these she liked, she was a super companion, humorous, mischievous, and incisive of thought. Such was not the case for many who disenchanted her in some method or whom she discovered to be not up to speed. Muriel knew all too nicely how her daughter may very well be devastatingly blunt and, to much less grateful units of ears, humiliating: “Rosalind’s hates, in addition to her friendships, tended to be enduring.”

Like many gifted younger folks, Rosalind Franklin erroneously assumed that her intense mental focus and fast, logical thoughts had been common and customary. All through her life, she had a tough time tolerating the mediocrity of others, typically on the expense of her skilled improvement. “Absurdities exasperated her,” Anne Sayre noticed. She responded to such folks and conditions with “fierce and cussed indignation.” In response to Muriel, folks whom Rosalind deemed to not be very vibrant irritated her to distraction due to her “pure effectivity in no matter she was doing was attribute, and he or she might by no means perceive why everybody couldn’t work as methodically, and with equal competence. She had little endurance with well-intentioned bungling and will by no means undergo fools gladly.”

***

In early 1947, Franklin moved to Paris and reported for obligation on the laboratory—or, as everybody there known as it, the labo. The ability was located at 12 Quai Henri IV, within the 4th arrondissement, and featured giant arched and leaded home windows looking onto the river Seine. She spent the following 4 years working alongside a cadre of French women and men and expatriates. She toiled as intensely as ever, reveling within the alternative to use her very good motor abilities, sharp thoughts, and love of experimental analysis to changing into one of many world’s most interesting X-ray crystallographers.

This was no simple activity. To start, one should determine an acceptable molecule to research. The crystalline construction of a specific molecule needs to be considerably uniform and comparatively giant in dimension; in any other case, a number of errors can be launched on the X-ray sample. As soon as an acceptable crystal is recognized, the crystallographer goals a beam of X-rays at it. Because the X-rays strike the electrons of the atoms making up that crystal, they’re scattered—and the scatterplot is recorded on a chunk of photographic paper positioned instantly behind the crystal. By painstakingly measuring the sizes, angles, and intensities of those scattered X-rays after which making use of advanced mathematical formulae to mapping them, the crystallographer develops a three-dimensional image of the crystal’s electron density. This, in flip, permits the positions of the atoms comprising the crystal to be decided, thus fixing that molecule’s construction.

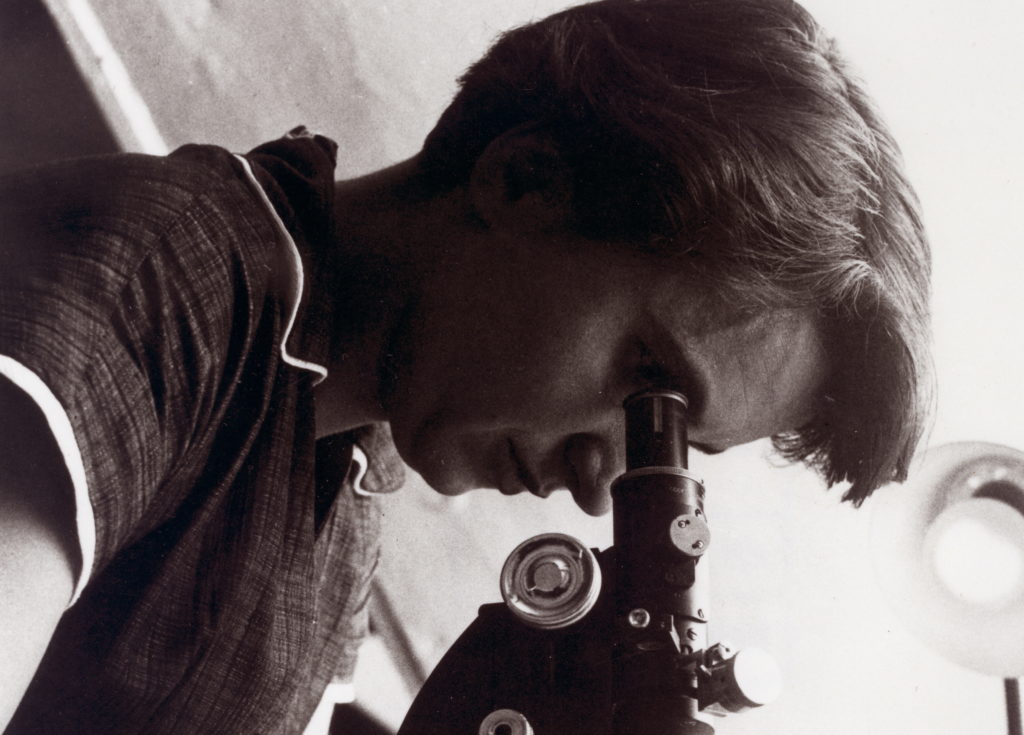

Rosalind Franklin in 1955. Picture by Picture 12/Common Photographs Group through Getty Photographs

Confounding issues additional, a single X-ray picture by no means gives the whole reply. The crystallographer should rotate the specimen stepwise by means of tons of of infinitesimally completely different angles over a spectrum of 180 (or extra) levels and take an X-ray image at each—and every presents its personal set of smudges or diffraction patterns, making the method each time-intensive, mind-numbing, and bodily cumbersome. Each certainly one of these tons of to hundreds of X-ray diffraction patterns was, at the moment, measured and analyzed by hand, eye, and a slide rule. If every step was not executed completely, artifacts or errors of measurement could be launched, resulting in improper solutions and conclusions. A blurred picture results in an excellent blurrier evaluation of how the atoms of that molecule are organized. Thankfully, Franklin was astoundingly adept at these strategies, and her outcomes had been very good. Her colleague, Vittorio Luzzati, an Italian Jewish crystallographer, was amazed by the outcomes that got here out of her “golden palms.” Her supervisor, Jacques Mering, who was additionally Jewish, described Franklin as certainly one of his greatest college students, somebody with a voracious urge for food for buying new data and remarkably skillful in each designing and executing advanced experiments.

In Paris, Franklin’s social life took on a continental aptitude. Fluent in French, she liked buying on the greengrocers and butchers, bolting down creamy pastries alongside the way in which, purchasing for the proper scarf or sweater, and getting misplaced exploring the byways of the Metropolis of Mild. She adopted Christian Dior’s “New Look” and took to carrying perfectly-cut attire that featured tight waistlines, small shoulders, and lengthy, full skirts. She absorbed the native tradition and politics, incessantly attending movies, performs, lectures, live shows, and artwork exhibitions with mates and potential suitors. Her vivacity, stylishness, and youthful magnificence weren’t misplaced on the boys in her life. Some have speculated that she developed a crush on the good-looking, flirtatious Jacques Mering, however as a result of he was married, albeit estranged from his spouse, she shortly retreated, sensing there was no probability for a romantic future.

For 3 of her 4 years in Paris, Franklin lived in a small room on the highest flooring of a home on rue Garancière, for the equal of about three kilos sterling a month. The landlady, a widow, had strict guidelines: no noise after 9:30 p.m., and Franklin might solely use the kitchen after the maid had ready the widow’s dinner. Regardless of such restrictions, Franklin discovered the best way to prepare dinner good soufflés and sometimes made dinner for mates. She had entry to a bath as soon as per week however in any other case used a tin basin stuffed with tepid water. The hire was a 3rd of what she would pay elsewhere and the placement was good: the sixth arrondissement, residence to the enduring Left Financial institution and the Sorbonne, located between the gardens of the Palais du Luxembourg and the vigorous cafes of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

Within the labo, women and men labored as equals in attending to their experiments, sharing meals and occasional, and debating scientific principle as if their lives trusted the end result. Luzzati (who, in 1953, would share an workplace with Crick on the Brooklyn Polytechnical Institute) recalled that deep inside Franklin was “a psychological knot” he might by no means unravel. She made many mates and a few enemies, Luzzati defined, largely as a result of “she was very sturdy and crushing, very demanding of herself and others, enduring not at all times to be favored.” Though he typically needed to clean over her verbal squabbles, he insisted that “she was an individual of utter honesty, incapable of violating her rules. Everyone who labored instantly together with her enveloped her in affection and respect.”

Franklin’s aventure parisienne was the antithesis of the very British conduct she later encountered at King’s Faculty, London. In response to the physicist Geoffrey Brown, who labored together with her each in Paris and at King’s, the labo “resembled a touring opera firm . . . they screamed, stamped their ft, quarreled, threw minor bits of apparatus at one another, burst into tears, fell into one another’s arms—all this in the middle of any dialogue.” On the finish of such heated debates, nevertheless, “the storms blew over leaving no grudges behind.”

On quite a lot of events, a lot to the hurt of her repute, Franklin imported such excessive drama to the King’s Faculty lab. One afternoon, she requested Brown if she might borrow his Tesla coil, an electrical circuit designed to provide the excessive voltages wanted for X-ray to work. She did not return it regardless of a number of well mannered entreaties from Brown, who wanted the coil for his personal experiments. Consequently, he recalled, “I went and took it again, and screwed it onto the wall. And she or he got here in, pulled it off and walked straight out.” He was nonetheless a lowly pupil and he or she was a postdoctoral fellow. Rank, clearly, had its privilege within the lab. The matter, Brown recalled, was resolved with out laborious emotions; he, his spouse, and Franklin grew to become quick mates. A number of of the opposite resentments she impressed at King’s, nevertheless, wouldn’t go so simply.

Excerpted from pp. 65-67, 82-84 in “The Secret of Life: Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, Francis Crick, and the Discovery of DNA’s Double Helix.” Copyright (c) 2021 by Howard Markel. Used with permission of the writer, W. W. Norton & Firm, Inc. All rights reserved.