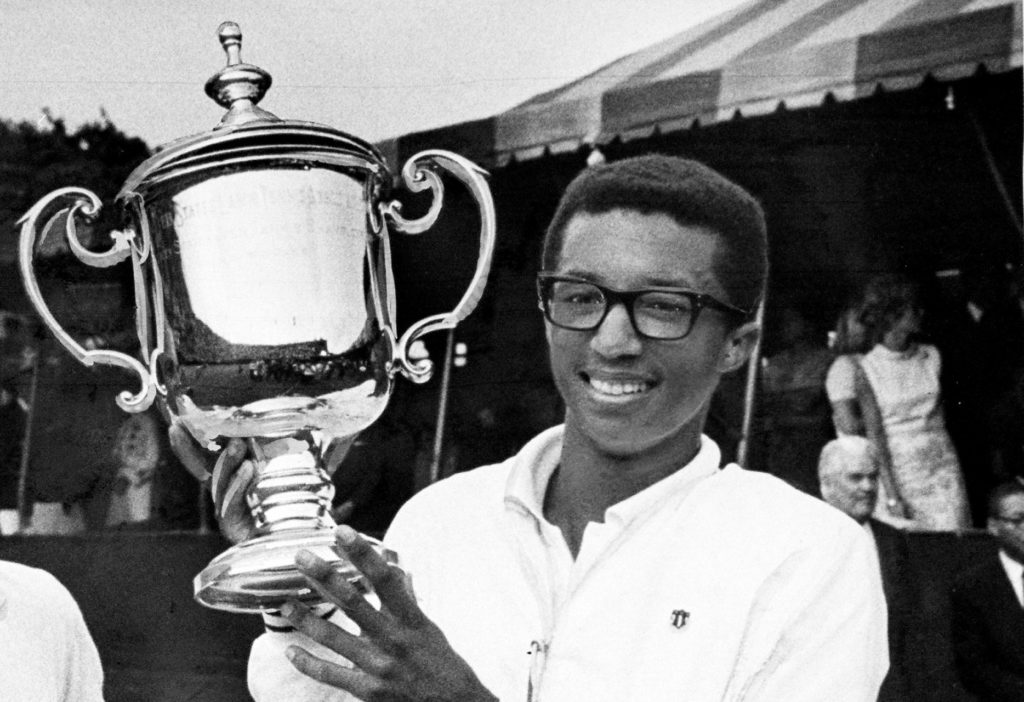

As another Wimbledon tournament nears its end, we celebrate the birthday of Arthur Ashe, the first African American man to play for the U.S. Davis Cup team, and the only African American to win the men’s singles title at the U.S. Open, the Australia Open and Wimbledon. When near the end of his storied life he discovered he was suffering from AIDS, Ashe transformed that losing match into victory — through activism and his concern for the health of others.

Ashe was born on July 10, 1943, in Richmond, Virginia. His father was a parks policeman, and his mother was a housekeeper who died when Arthur was only 6. As a boy and man growing up in segregated Richmond of the 1940s and 1950s, Arthur contended with open racism that often threatened to halt his progress in what was then a sport of wealthy, rich, white people. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, however, many considered Ashe to be the best tennis player in the world.

Ashe suffered his first heart attack in July of 1976, when he was only 33. His doctors immediately turned to the medical histories of his mother — who died of complications from surgery at the age of 27 — and his father — who had two heart attacks at age 55 and 59, the second occurring only a week before his son’s. After catheterizing Arthur’s coronary vessels, the cardiologist found one cardiac artery completely closed, a second one was 95 percent closed, and a third 50 percent closed. He underwent a quadruple coronary artery bypass surgery in 1979, a few years before the first cases of AIDS were recognized and several more before the nation’s blood supply was scrutinized for blood-borne viruses, such as HIV and the hepatitis viruses. But this procedure failed to correct his chest pain and he underwent a second surgery, a double bypass graft, in 1983.

READ MORE: How winning the U.S. Open gave Arthur Ashe the spotlight to speak out against injustice

Unfortunately, one of the many transfusions Ashe received during or after his surgery was tainted with HIV. During the early 1980s, it must be noted, doctors were still stymied by the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of AIDS. In 1988, Ashe developed symptoms of right arm paralysis that was later found to be caused by the relatively rare, opportunistic fungal infection toxoplasmosis. A blood test explained why: Arthur was HIV-positive and in the throes of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Because Arthur and his wife, the photographer Jeanne Moutoussamy, had recently adopted a baby girl named Camera, they elected to keep the diagnosis quiet.

They managed until the spring of 1992, when word came out that USA Today was planning a front-page story on his illness. In response, on April 8, Ashe decided to tell his story on his terms, by making the announcement himself.

Ashe managed to harness his exposure into the creation of the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS. He also created inner city tennis and AIDS prevention programs. Indeed, he spent the last year of his life advocating healthier life choices, safer sex methods, and debunking the fallacy that AIDS only affected gay men or intravenous drug users. He even made a floor speech to this effect at the United Nations World AIDS Day on Dec. 8, 1992.

On Feb. 6, 1993, Arthur Ashe died from AIDS-related pneumonia. He was only 49. In his New York Times obituary, Ashe was compared to Jackie Robinson, who opened the door for a whole cadre of excellent minority players to play in the major leagues. Ashe, on the other hand, was virtually alone in terms of being the “the only prominent black tennis player of his era. It was a position that left him feeling ostracized at times, he said, by both blacks and whites…but Ashe served as a beacon for generations of black tennis players,” the Times reported.

Indeed, Ashe served as a beacon of kindness and courage for generations of African Americans, tennis players and fans, HIV/AIDS patients, nurses, health care workers, and doctors like me who attended AIDS clinics, and nearly everyone else acquainted with his story.

Of all the so-called “heroes” lining Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, there is one that outpowers them all: the statue of Arthur Ashe. In his eloquent memoir, “Days of Grace,” Ashe recorded his own vision of heroism:

“True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost, but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.”

What more can be said of this remarkable man than, “Match, Ashe!”