TAIPEI—When buyers need chips in a pinch, they turn to

Erik

Drown, a middleman who is able to source scarce parts.

Mr. Drown’s decades of experience are now up against one of the worst semiconductor shortages ever. Asked recently by a client to help find 1,200 chips in a matter of days, Mr. Drown scoured his industry contacts. He couldn’t find all the needed chips but was able to get preliminary price quotes on about half.

It is a painful truth for businesses world-wide: They need chips but can’t find them. Making matters worse is that the typical problem solvers—chip brokers and middlemen such as Mr. Drown—find themselves in some cases just as perplexed and empty-handed. Yet they are busier and making more profits than ever.

“A lot of companies that would never go to someone like me, they have to because if they don’t, they’re not going to survive,” said Mr. Drown, global sourcing director at Select Technology Inc., an electronic-components distributor based in Rowley, Mass.

A breakdown in the typical distribution of chips adds extra layers of complication to a monthslong shortage that remains widespread and is likely to continue through the end of the year, say chip makers, wholesalers and buyers.

During normal times, the largest chip makers such as

Intel Corp.

or

Samsung Electronics Co.

ship semiconductors directly to their deep-pocketed buyers and contracted wholesalers. Leftover supply generally went to other middlemen that cater to smaller buyers. Most years, there was plenty to go around.

But now, it is a free-for-all. The biggest companies have seen their direct access cut off or limited. As a result, they are looking for extra help from wholesalers contracted by the chip makers, middlemen known in the industry as authorized distributors.

Avnet Inc.,

an authorized distributor for Intel and Broadcom Inc., has seen a surge in large buyers that previously didn’t need outside assistance locating chips. It is uncharted territory for those clients, having to hedge against supply chain disruptions or keep tabs on a host of different materials, said

Peggy Carrieres,

Avnet’s vice president for global sales enablement.

“They are wanting us to deal with it,” Ms. Carrieres said.

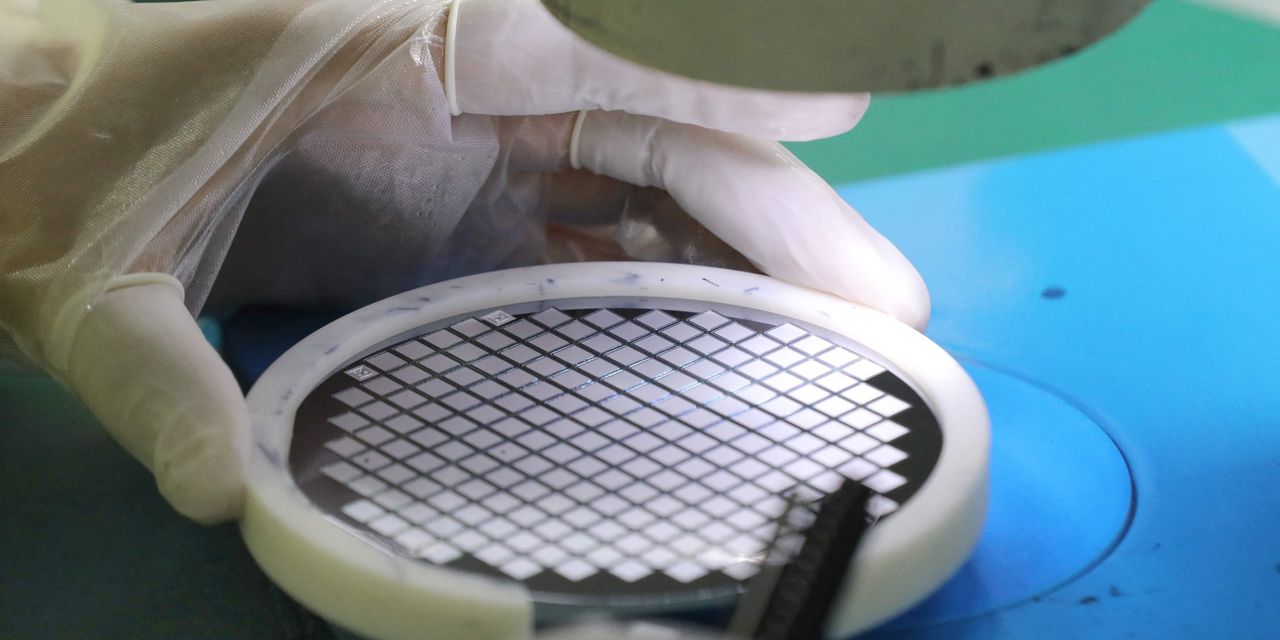

A worker makes a chip at a factory in China’s Jiangsu province on March 17.

Photo:

Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Despite the scarcity, higher prices and shipping volumes have boosted bottom lines for distributors, which typically take a 10% markup on chips, and even more when providing consulting for alternative parts or product designs, estimated

Peter Hanbury,

a partner at Bain & Co. who specializes in the semiconductor supply chain.

Arrow Electronics Inc.,

one of the industry’s biggest players, said global component sales reached a record $6.4 billion in the first three months of the year, up 42% from a year earlier. The Colorado-based firm’s operating income for its global components business rose more than 70% during the same period. For the quarter ended March 31, Avnet said its sales rose 14% from a year earlier to $4.9 billion.

Big buyers have also been forced to use middlemen that rely on indirect methods to procure components, such as purchasing unused chips from goods manufacturers that bought more than they needed. Because the independent brokers aren’t buying directly from chip makers, these secondhand transactions can be costlier and bring greater authenticity risks.

The $442 billion chip industry has traditionally been turbulent. But consumer demand from pandemic shifts to online work and life, coupled with a strong economic recovery, caught buyers and chip makers off guard over the past year. Supply can’t increase quickly enough. So prices have skyrocketed.

Semiconductors that power electronic displays have surged in price by as much as 40% in the first half of 2021 from a year earlier, market researcher Counterpoint Research says. During the same period, some image sensors and processors used in phones and personal computers have seen prices increase by 15% to 20%, Counterpoint estimates, while memory-chip prices have risen 5% to 10%.

The situation is even worse for car makers, which are lacking chips such as microcontrollers used in vehicle ignitions or brake systems. Brokers are quoting prices that are five times higher than they were before the pandemic for auto chips, and in some extreme cases 20 times more, said

Ambrose Conroy,

founder of Las Vegas-based supply-chain consulting firm Seraph.

Subaru cars sit at a storage lot in Richmond, Calif., on May 14. Car makers around the world have been struggling to find semiconductors.

Photo:

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Prices have surged so much that

Jens Gamperl

will show disbelieving buyers the wholesale price that his online-chip selling platform, Sourcengine, pays before taking any markups. For example, one flash-memory chip that would normally cost 50 cents was going for $38 on Sourcengine at one point in April, Mr. Gamperl said. The next day it leapt to $49.50.

“The customer is always suspicious that you try to take advantage of the situation,” Mr. Gamperl said.

Prices are often staying high because companies can’t afford to wait to make purchases.

Dan Hetnar,

senior buyer for a U.S. circuit-board manufacturer, used a broker to buy some 1,500 microchips—at more than triple the typical price of $2.75 per part. Otherwise, if pushed to go through an authorized distributor that deals directly with the chip makers, the parts wouldn’t have been available for 45 weeks.

“It’s the one thing I need,” Mr. Hetnar said.

The steep price swings reflect how scarcely available the components are—and even so, how much new business is rolling in for many middlemen. Direct Components Inc., a Tampa, Fla.-based chip broker, has seen a tripling of clients in the past year, including many big buyers that hadn’t reached out before, said the firm’s founder,

Aaron Nursey.

“A year ago they really wouldn’t give us the time of day,” he said. “Now they’re coming to us.”

Write to Stephanie Yang at stephanie.yang@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8