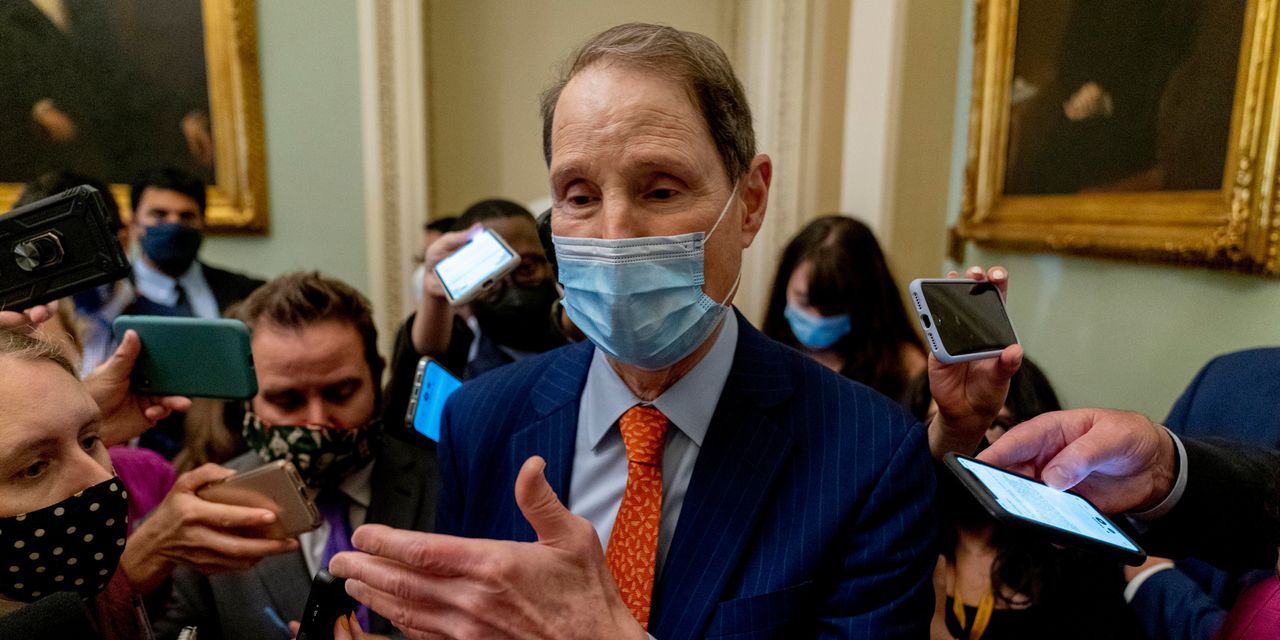

WASHINGTON—Democrats are poised to consider a plan that would upend tax rules for the wealthiest Americans, as Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden makes a late bid for a new capital-gains tax in President Biden’s social-spending and climate-change legislation.

Mr. Wyden’s detailed proposal—annual income taxes on about 700 billionaires’ unsold publicly traded assets such as stocks—arrives as Democrats are struggling to find up to $2 trillion over a decade to cover the cost of their agenda. They have plenty of ideas that would exceed that figure, but precious few that can muster the support of enough Democrats to get through the narrowly divided Congress.

Lawmakers’ reaction in the coming days will determine whether the idea advances or whether it joins the pile of other tax proposals that Democrats have floated and cast aside this year amid objections from moderates, progressives or both.

Mr. Wyden’s 107-page plan would eliminate billionaires’ ability to defer capital-gains taxes indefinitely, and it would impose multibillion-dollar tax bills on people such as Amazon.com Inc. founder Jeff Bezos and Tesla Inc. CEO Elon Musk, who has criticized the plan. It is expected to raise hundreds of billions of dollars over a decade, though the actual amount would depend on stock prices and on whether courts rule the tax unconstitutional.

The money would come from the wealthiest taxpayers, many of whom currently can keep their reported income and tax bills low. Under today’s tax system, they don’t have to pay capital-gains taxes unless they sell their assets, and they can borrow against that wealth to finance their lifestyles.

The proposal, if implemented, would likely generate a large chunk of revenue in the first few years from company founders who would pay tax on the high value of their businesses against a zero or very low cost basis. That includes people who started companies in garages and dorm rooms and turned them into tech giants.

The plan would accelerate the tax collection on future gains and also impose taxes on gains now that would have been avoided by deaths that won’t occur for decades. After that, the annual revenue from the plan would depend on fluctuating asset values of tradable stocks.

“The Billionaires Income Tax would ensure billionaires pay tax every year, just like working Americans,” said Mr. Wyden (D., Ore.). “No working person in America thinks it’s right that they pay their taxes and billionaires don’t.”

Republicans have said that the idea would hurt economic growth, and House Democrats have watched the Senate tax conversation with frustration. The House Ways and Means Committee approved its proposed tax increases last month, relying on higher tax rates on corporations, high-income individuals and capital gains that hit the very rich but did little to focus on billionaires’ unrealized capital gains.

“‘No working person in America thinks it’s right that they pay their taxes and billionaires don’t.’”

House members spurned President Biden’s idea of taxing capital gains at death and are now seeing the Senate consider an even more transformative capital-gains tax-policy change on a tight deadline.

“This is the public relations idea,” said Rep. Dan Kildee (D., Mich.). “It’s not a substantive policy suggestion.”

Here’s how the Wyden plan would work.

It would start in 2022 and apply to people who have a net worth of $1 billion or annual income of $100 million for the three prior consecutive years—2019, 2020 and 2021 to start. They would remain in the new tax system unless they had three straight years in which their assets and income fell below half of those thresholds.

First, as the new system starts, affected people would have to pay a tax as if they had sold their publicly traded assets. So someone who bought $2 billion worth of stock in 2010 that is now worth $20 billion would have $18 billion added to their income, taxed at the top long-term capital-gains rate of 23.8%. That $4.3 billion initial tax could be paid over five years.

Then, each year, they would have to pay a tax on the gain in value for that year. Unrealized losses could be carried forward to offset future gains or backward up to three years to offset past gains and claim refunds.

A different set of rules applies to nontraded assets such as real estate and closely held businesses. Those gains wouldn’t be taxed each year, avoiding the difficulty of assessing value annually.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

Are you adjusting your portfolio based on the proposal for an unrealized gains tax? Join the conversation below.

Instead, they would be taxed as capital gains when sold or transferred or when the person dies. Without any other change, that rule would create a tax preference for such assets over annually taxed publicly traded stock because the tax on real estate and businesses could be deferred. The Wyden plan includes an interest charge on nontraded assets such as real estate, and that is designed to equalize the burden on those assets with the burden on publicly traded assets.

The proposal would add the interest charge to the regular tax rate but cap the total tax at 49% of the gain in value. That cap plus the way the interest is calculated could give people an incentive to shift to nontraded assets. But the rules for losses are less generous than for publicly traded assets.

The Wyden plan includes a series of rules designed to limit billionaires’ ability to escape the tax, and they would be tested quickly as the well-financed taxpayers battled with the Internal Revenue Service over what they owe.

For example, gifts and bequests, except to spouses, would be considered as triggering a capital-gains tax. Donations to charity wouldn’t.

Many trusts would be subject to this tax system if they had at least $100 million in assets or $10 million in income; those lower thresholds are aimed at preventing billionaires from splitting their assets among trusts to avoid the tax.

The plan also has rules limiting how billionaires can use trusts, deferred compensation, annuities, life insurance, tax-advantaged small-business stock and the tax breaks in low-income “opportunity zones” created in the 2017 tax law.

Mike Kosnitzky, co-head of the private-wealth practice at law firm Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, has spent the past few days talking with a dozen or so ultrawealthy clients potentially affected by the plan.

“There are some who want to be very proactive and do whatever’s necessary” to minimize the tax, Mr. Kosnitzky said. “Some are resolved to saying, ‘Whatever it’s going to be, it’s going to be.’ Those are mostly my Democrat clients.”

The proposal would motivate the very wealthy to shift from publicly traded assets into other assets that wouldn’t be taxed each year, he said. They may still be able to use complex strategies they have turned to for years like moving assets into foundations and other tax-friendly vehicles. New approaches will likely crop up.

“Smart investment bankers and asset managers are already thinking about how to financially engineer products that will emulate existing stocks but be hard to value,” Mr. Kosnitzky said.

—Natalie Andrews and Rachel Louise Ensign contributed to this article.

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com

Copyright ©2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8