SINGAPORE – Even before the Covid-19 pandemic and talk of so-called “vaccine passports” that serve to digitally prove a person has been vaccinated against the coronavirus to facilitate travel between countries, work on a more all-encompassing digital passport had already begun.

While a vaccine passport cannot replace a person’s physical passport for travel, a digital passport could, to an extent.

This might mean a traveller using his smartphone and having his face scanned to clear immigration.

The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), a United Nations agency that oversees global commercial aviation, has been looking into digital passports for four to five years.

In November last year, it was reported that ICAO had endorsed some specifications in a step towards developing such digital documents, dubbed “digital travel credentials”.

In Singapore, the idea that the country’s national identification system, Singpass, could eventually become a digital passport has also been raised in recent months.

In March, then Minister-in-charge of the Smart Nation Initiative Vivian Balakrishnan said that with all the features built into Singpass, “it is not a stretch to imagine that (Singpass) will eventually evolve into an international digital identity or… passport”.

Minister for Communications and Information Josephine Teo in August reiterated this possibility.

The Government Technology Agency said in March that Singapore is in talks with Australia and Britain on developing a digital passport, although this is still some years away from being ready.

What is needed for a digital passport and how could it work?

Verifying identities

A digital passport needs to be able to verify and authenticate a traveller’s identity. With Covid-19 deterring face-to-face interactions, countries need to think about developing systems to do this in a contactless way.

“There is an opportunity for countries to develop digital passports that sit in the traveller’s mobile phone,” said Mr Frederic Ho, vice-president of Asia-Pacific at identity verification company Jumio Corp, adding that many people globally use such handsets now.

He said that smartphone features, like using its camera to scan a person’s face, can help verify a person’s biometric information linked to the digital passport and a government database to ensure the person behind the screen is who he says he is.

Crooks might try to use an image or video of a person’s face to trick the face scanning process. But there are anti-spoofing solutions that can do a “liveness detection” to confirm a person’s physical presence behind the screen.

This would be an evolution of current biometric or electronic passports (e-passports) used now.

Such passport booklets have encrypted chips that contain a traveller’s information, like face or eye maps and fingerprint data. These can be checked against a traveller by scanning his biometrics at automated checkpoint gantries.

A digital passport platform would need to ensure that the information on it cannot be altered without authorisation, said Mr Angus McDougall, regional vice-president for Asia Pacific at Entrust, another identity verification company.

A traveller’s personal records that are stored and in transit must be secured with encryption and the data in the digital passport in his phone needs to be encrypted too.

And for immigration officers to access travellers’ data, multi-factor authentication is required, Mr McDougall said.

Mutual recognition

For developing digital passports, Mr Ho said Singpass is great for verifying the identities of citizens. For example, it has a feature that does so by comparing face scans against the Government’s database.

But one hurdle for digital passports for border clearance is that they need to be mutually recognised by other countries, he said.

This is an issue with vaccine passports now, Mr Ho said, adding that such digital health certificates are like travel visas. Various countries have different approaches to validating visa applications and possibly for vaccine passports.

To address such inter-operability issues for digital passports, Mr McDougall said one way is to look to common standards set by international organisations such as ICAO.

How it could work

ICAO’s digital travel credential could pave the way for standardised digital passports recognised globally.

The credential is an encrypted file that is a replica of the information from the chip embedded in a traveller’s e-passport. This means the credential contains his identity and biometric data.

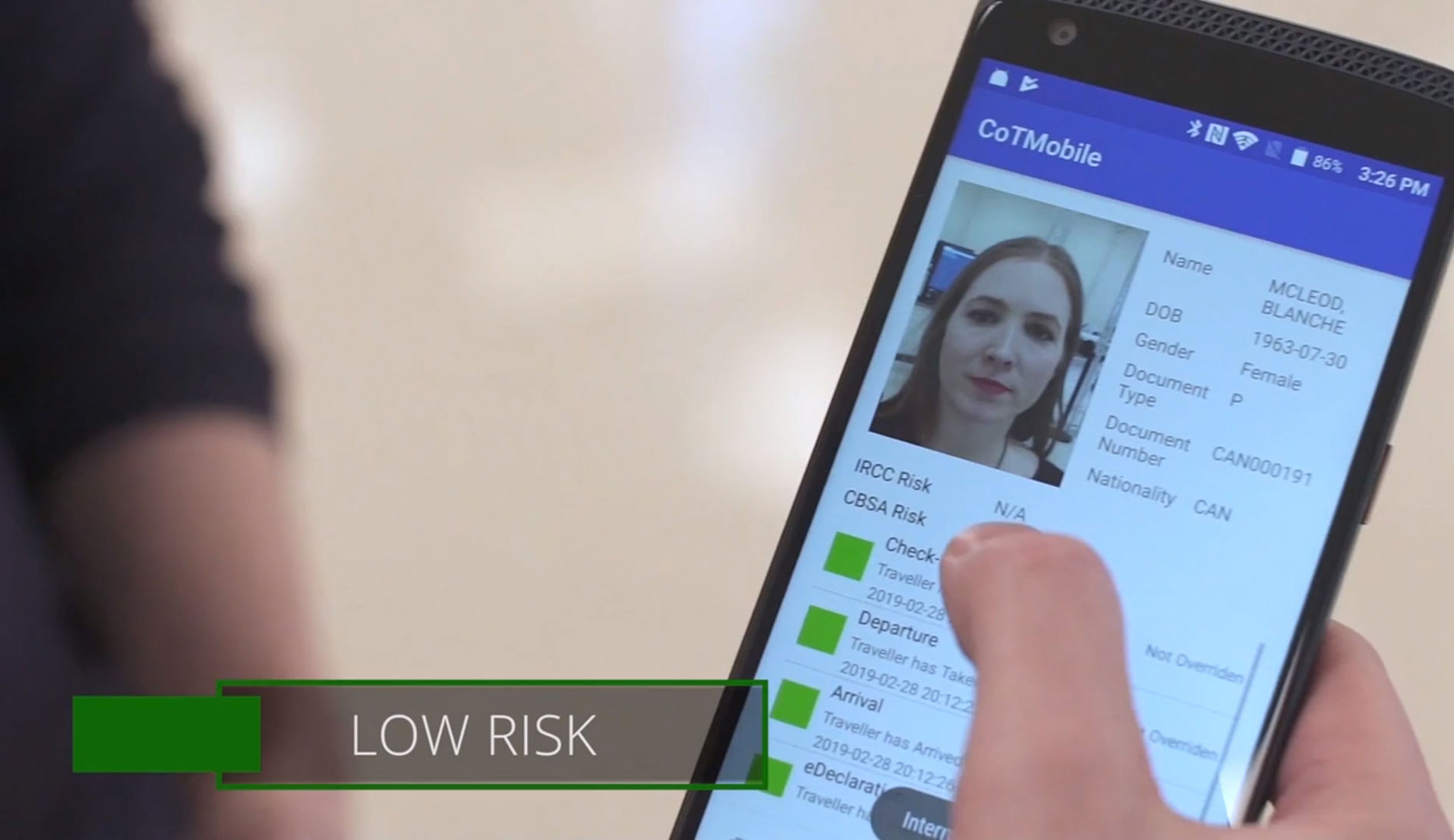

An ongoing trial in Canada sheds some light on one way the digital travel credential could work. The Canadian Border Services Agency is working with private and public sector organisations, including Entrust, on this.

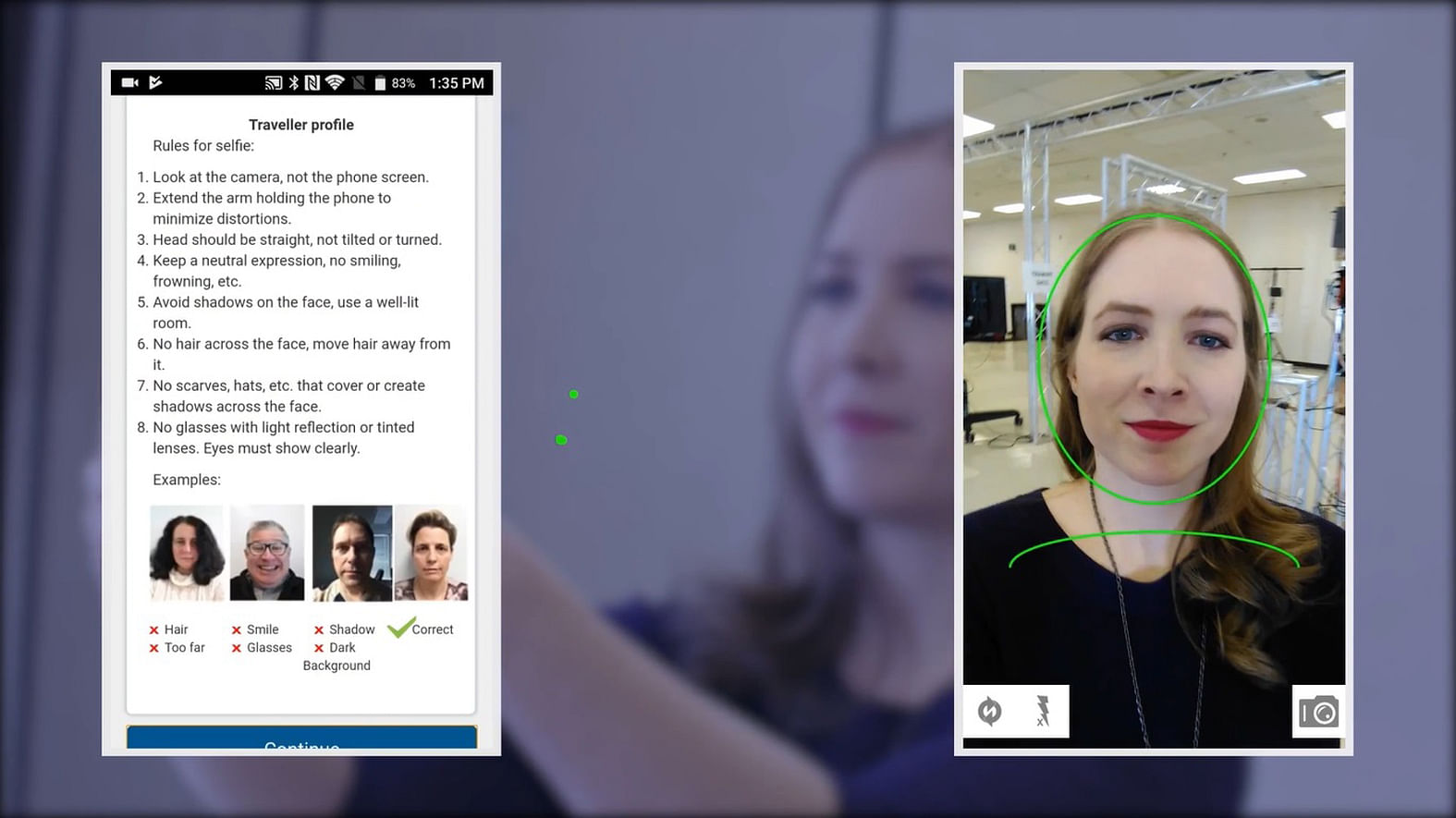

In one scenario, the process starts with a traveller downloading an immigration mobile app before his flight. He uses his phone’s camera to scan the page of his passport that has his photo, taps his phone on his e-passport so that it can read the booklet’s chip using near-field communication, and takes a selfie with the app.

These steps help verify the traveller’s identity by checking against a government database.

If the verifications are successful, a digital travel credential is created. The encrypted credential is stored in the app and can stand in for the e-passport. A copy of the encrypted credential and other supporting travel documents are also stored in the backend. Only approved staff like those from the immigration authorities have the means to decode the encryption.

The traveller’s face becomes the main way to verify his identity later, with the digital travel credential in his phone app and his physical e-passport serving as back-ups.

When the traveller is ready to fly, he checks into the airport at the airline counter or self-service kiosk. His face is scanned and checked against the digital travel credential stored. If successful, he gets his boarding pass, deposits his luggage and heads to border clearance.

There, he walks through corridors of cameras and screens where his face gets scanned at several points to confirm his identity.

Prompts on screens and his app tell him where to go next after his face is scanned.

At the boarding gate, he again has his face scanned. If nothing goes awry, he boards the plane without having to show his physical passport and without much contact with checkpoint officers.

Roving immigration officers will observe passing travellers in the border clearance zone. If they detect suspicious behaviour, an officer can step in to manually check the traveller’s physical passport or scan his phone’s digital travel credential and interview him.

If the traveller is flagged as a risk, such as being a suspected drug mule, he can be directed to another area for checks.

How long the digital travel credential will remain, such as on the traveller’s phone, would have to depend on a country’s policies.

This example represents one of several early ways to implement ICAO’s digital travel credential.

The ultimate goal is to eventually develop specifications that do away with the physical passport, “but we are still many years out from that”, said Mr McDougall.

In the meantime, Singapore’s Immigration and Checkpoints Authority is looking into a way for Singaporeans to pass through immigration gates without needing to produce their passports from next year.

Called the New Clearance Concept, it primarily involves using iris or facial scans to verify identities. In a step towards this, it was announced in October last year that all immigration checkpoints here had replaced fingerprint scans with facial and iris scans.