Ireland’s healthcare service is still slowly restoring its technology systems five weeks after suffering a ransomware attack, highlighting the painful process of bringing back online thousands of damaged computers.

Two weeks ago, some of the technology systems in Children’s Health Ireland’s three hospitals were restored but are now operating more slowly than before, said Eilish Hardman, chief executive of the group. Around a third of scheduled outpatient appointments have been postponed, 80% of hardware devices replaced and internal email still isn’t running normally, she added. It will be several weeks until all computer systems work again, she said.

Doctors and lab technicians used pen and paper for most of the past month, she said, and corporate and administration staff hand-carried lab reports to clinicians.

“It sent us back almost into the ’70s, being paper-based,” she said.

On the morning of May 14, attackers using the Conti ransomware strain took down the Irish Health Service Executive, the country’s public healthcare system, resulting in cancellations and delays of medical appointments around the country. As of Thursday, around 55% of HSE’s servers used for important medical system infrastructure had been restored and 58% of its servers had been decrypted.

“It’s been a 35-day hell,” Paul Reid, the healthcare executive’s director general, told a news conference on Thursday. “It will continue to be a longer haul over the next few weeks, if not likely into months,” he said.

Ransomware attacks often leave victims struggling to bring back compromised technology systems for long periods. The Scottish Environment Protection Agency was also attacked by a Conti gang last year on Christmas Eve and is still bringing back some of its systems, Terry A’Hearn, the agency’s chief executive, said at the WSJ Pro Cybersecurity Executive Forum this month.

“Knowing early how long it would take to recover would have been helpful in managing some of the impacts,” he said.

AT HSE, security and IT staff have been working to bring back more than 2,000 separate computer systems and applications, some of which were decades old. The organization is rebuilding some systems and upgrading others. Hospitals and healthcare offices with older computer systems suffered more disruption from the ransomware attack than newer applications. Three cloud-based platforms built in the past year for Covid-19 contact tracing, testing and vaccines weren’t affected.

The HSE’s large IT infrastructure includes many applications that connect and use data from other applications, which can make it difficult to properly restore services if others are still down, said Simon Woodworth, a lecturer in business information systems at University College Cork who conducts research with the HSE. “What you have is a system that’s both complex and also brittle,” he said. “It breaks easily and if one part breaks, another part breaks.”

For systems already restored, there are other risks, including making sure information taken in writing is correctly entered into patient records, said Anne O’Connor, the HSE’s chief operating officer, speaking at the news conference.

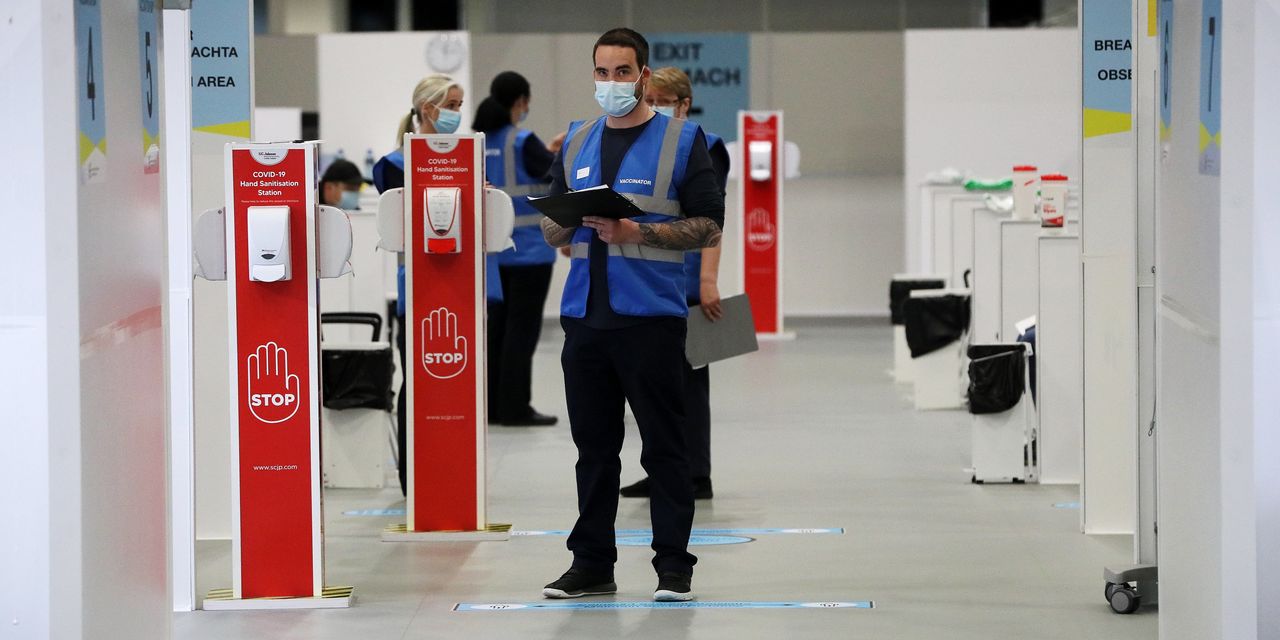

Paul Reid, director general of Ireland’s Health Service Executive

Photo:

Niall Carson/Zuma Press

Hackers initially threatened to publish data they stole from the healthcare system online if officials didn’t pay a ransom fee of around $20 million, according to screenshots of the demand that the ransomware group posted online. Conti ransomware gangs have previously stiffed victims, and in one case restored only a small portion of encrypted data after a victim paid the ransom, according to a report published Friday by cybersecurity company

Palo Alto Networks Inc.

Top HSE and government officials were adamant that they wouldn’t pay any ransom, saying doing so would violate government policy.

Government officials and the Irish police warned the public that their private health information could be posted on the internet. Ireland’s data protection commissioner published a blog post about how individuals should deal with threats from scammers trying to capitalize on their data. So far, hackers haven’t posted patient data from the HSE.

One week after the attack, hackers offered the decryption key free of charge and without explanation.

Wary HSE technologists worked with external cybersecurity consultants to make sure the key was safe to use and wouldn’t unleash more malware, Ossian Smyth, Irish minister of state for communications, said in an interview.

While Irish healthcare and government officials were relieved that sensitive data from millions of citizens wasn’t published online, they now have to pay several multiples of the hackers’ ransom demand, Mr. Smyth said. Because the decryptor works, although slowly, the government doesn’t expect the HSE to lose data, he added.

Mr. Reid previously said the recovery efforts would cost at least 100 million euros, equivalent to $119 million.

“Even when you’ve got the key, unlock the data, prevent the two threats, you’re still left with destruction to the service,” he said, referring to the hackers’ threat to keep data encrypted and publish stolen information. “Once you get attacked by these people, there isn’t a clean way out,” he said.

Doctors and staff in the three childrens’ hospitals have been working hard and adapting to manual workarounds because of the technology problems, Ms. Hardiman said. She hopes some can take time off over the summer. “It’s been a tough 15-16 months now with Covid, and this was a devastating cyberattack,” she said.

Write to Catherine Stupp at Catherine.Stupp@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8