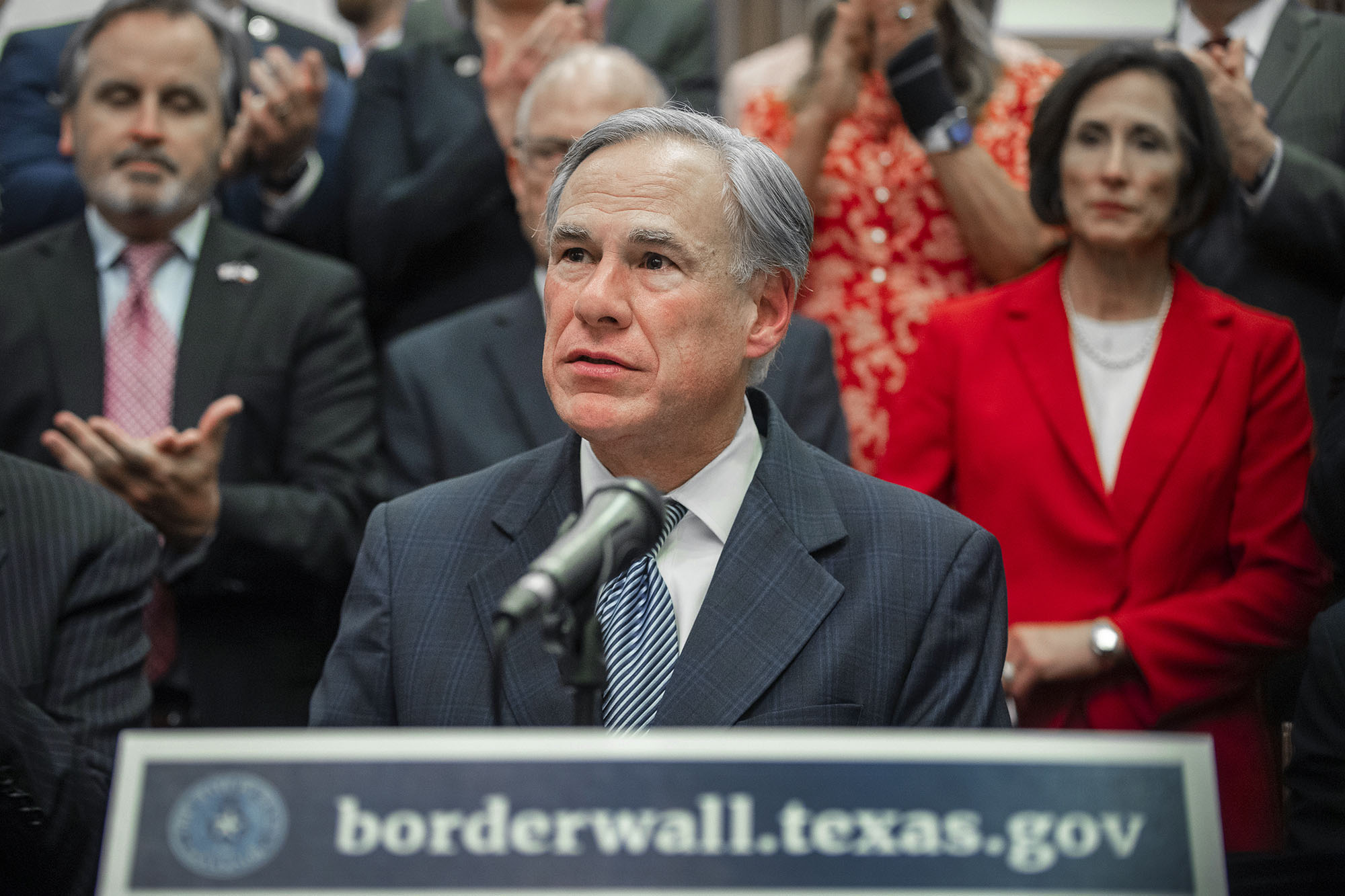

“The federal government must solve the federal problem caused by the Biden administration’s disastrous open-border policies,” Abbott wrote in a recent letter to HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra. “Texas will not be commandeered into federal government service.”

Officials in several other GOP-led states have declined to aid HHS’ months-long effort to arrange housing and services for tens of thousands of migrant children in federal care, privately rejecting the government’s appeals for help and in some cases publicly criticizing the possibility of unaccompanied children entering their states.

But Texas’s order represents the most drastic attempt by a state to decouple itself from a long-running federal program that relies on state-licensed organizations to shelter migrant children until they can be placed with guardians. HHS has accused Abbott of launching a “direct attack” on the administration’s effort to care for record numbers of unaccompanied children crossing the southern border and said it’s consulting with the Justice Department on necessary legal action.

Under Abbott’s plan, 52 shelters across the state would be forced to halt care for unaccompanied minors or be stripped of the licenses currently needed to remain open.

That would leave more than a quarter of the nation’s entire population of migrant kids without anywhere to stay. Texas hasn’t offered any housing alternatives, with Abbott insisting that it’s HHS’ responsibility.

He has also vowed to build a U.S.-Mexico border wall, boasting earlier this month that Texas is “doing more than any other state has ever done to respond to these challenges along the border.”

HHS said it is still awaiting a response to more than two dozen questions that Deputy General Counsel Paul Rodriguez sent to Abbott and other Texas officials seeking specifics on how they planned to implement the order.

“We are exploring our options, for the sake of protecting the safety and well-being of unaccompanied children at licensed facilities in Texas,” a spokesperson said.

Abbott’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Thousands of children could be scattered to shelters around the country if the Texas order were to take effect, former officials and advocates for the unaccompanied minors said. And with the administration already struggling to manage an influx of kids, those destinations would likely be emergency facilities constructed on military bases and in convention centers that have faced scrutiny from both Republicans and Democrats over their conditions.

“It’s very hard to see what’s accomplished,” said Mark Greenberg, a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute who led HHS’ Administration for Children and Families during the Obama administration. “There’s been broad agreement that it’s a good thing for children to be in licensed facilities — which are regulated and monitored — and this effort just makes that harder.”

Abbott previously criticized the emergency sites that HHS rushed to open in response to the sharp rise of border arrivals, calling one shelter in Texas “a health and safety nightmare” just two-and-a-half months ago.

But in his most recent letter to Becerra, Abbott cited the emergency facilities as justification for withdrawing all state-level support, arguing that Texas shouldn’t also have to offer up its own licensed facilities.

“The federal government cannot force a state to do the federal government’s job,” he wrote.

HHS has warned Abbott that his order appears to violate various federal laws, a view shared by legal experts who said it’s guaranteed to be challenged in court as soon as it takes effect.

“At the most basic level, states aren’t allowed to discriminate against federal contractors,” said Spencer Amdur, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Immigrants’ Rights Project. “They also can’t obstruct in any way the federal government’s ability to work with private entities.”

Still, the Texas order has sown confusion among the organizations running shelters that rely solely on contracts with the federal government to care for unaccompanied children and now must devise a fallback plan within weeks.

State officials have also struggled with how to enforce Abbott’s order, which offered no specific guidance on how it should be implemented and little justification beyond criticizing the Biden administration for its “failure to secure the border.”

Abbott in a June 11 letter to Becerra denied that the order would result in facilities being shut down altogether, saying only that they would no longer be licensed by the state. But a notice sent nine days earlier by Texas’ health agency to shelter organizations instructed them to wind down all activities tied to unaccompanied minors.

One major shelter operator, BCFS, was separately warned by a state health official that it would be fined if it continued to house migrant children beyond Aug. 31, the organization told POLITICO.

A spokesperson for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission declined to offer details on how it planned to enforce Abbott’s order, saying the agency is still working on an implementation process.

Democrats, meanwhile, have blasted Abbott over what they argue is a political ploy to fortify his standing with the Republican base at the expense of vulnerable children — a move made more evident by Trump’s planned return to the border this week.

“It’s obviously very alarming, destructive and very harmful for children in need,” said Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), who on Friday hosted Vice President Kamala Harris’ own border visit. “The governor long ago abandoned governing, and he is focused solely on fighting the culture wars.”

Some Republicans on Capitol Hill have also distanced themselves from Abbott’s plan, even as they’ve enthusiastically embraced broader criticisms of the administration’s border policy.

Asked about the prospect of yanking facilities’ licenses, Texas GOP Rep. Dan Crenshaw told POLITICO he hadn’t looked into it and wasn’t a “state rep[resentative].” Sen. Ted Cruz also said he’d hadn’t talked with Abbott about the order and declined to say whether he supported it.

Nevertheless, the confrontation risks pulling the administration into a drawn-out fight over an immigration challenge that it has worked hard to tamp down across the first months of Biden’s presidency.

After hitting a record high of almost 23,000 unaccompanied children in federal custody in April, the health department has winnowed the population down below 15,000. That’s a level that remains significantly higher than normal, but has allowed it to move more children out of emergency facilities and into higher-quality licensed facilities.

Yet even as it lays the groundwork for a swift legal challenge, officials conceded that there’s little HHS can do to head off Abbott’s order now before it takes effect — setting the stage for a protracted clash over the border that could carry well into the fall.

“The politics is everything,” Amdur said. “I think, basically, they’re doing this to make the administration look bad.”