SEOUL (AFP) – Award-winning film-maker Yang Yong-hi was simply six years previous when she watched her eldest brother depart Japan for North Korea as one among 200 “human items” for chief Kim Il Sung’s sixtieth birthday.

Because the North Korean anthem blared, by bursts of confetti, he handed her a notice earlier than his ferry departed Niigata port: “Yong-hi, take heed to plenty of music. Watch as many films as you need.”

It was 1972, a 12 months after her dad and mom – members of the ethnic Korean “Zainichi” neighborhood in Japan – had despatched their different two sons the identical manner, lured by the Kim regime’s promise of a socialist paradise with free training, healthcare and jobs for all. The boys by no means moved again.

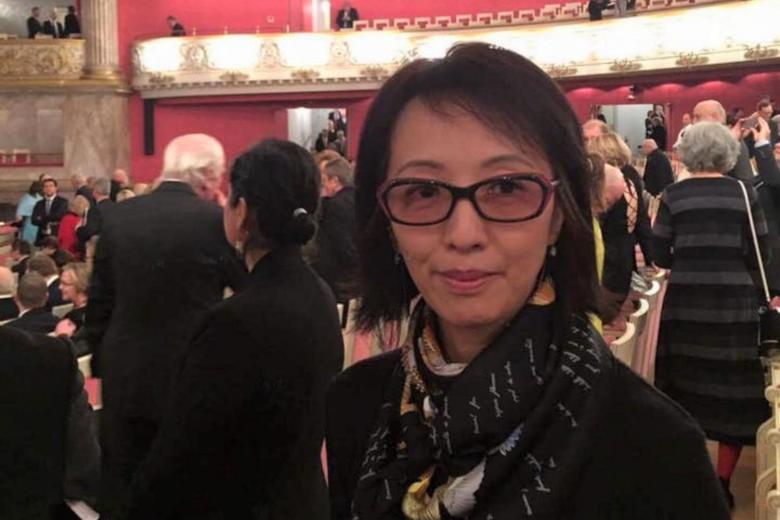

“My dad and mom devoted their complete lives to an entity that got here up with such a mindless challenge and compelled them to sacrifice their very own kids for it,” Yang, now 57, stated.

The trauma of being ripped other than her siblings reverberates in all of Osaka-born Yang’s movies, which doc the struggling of her household throughout generations – from the tip of Japanese colonial rule to many years after the break up of the Korean peninsula.

Her father was a outstanding pro-North Korean activist in Osaka, and had despatched his sons to dwell there within the Nineteen Seventies as a part of a repatriation programme organised by Pyongyang and Tokyo.

About 93,000 Japan-based ethnic Koreans left for North Korea below the scheme between 1959 and 1984. Yang’s eldest brother was amongst 200 college college students specifically chosen to honour Kim. The regime’s guarantees got here to nearly nothing, however the Zainichi arrivals had been pressured to remain. Their households may do little to convey them again.

Yang’s dad and mom “had no selection after having already despatched their kids. To maintain the children secure (in North Korea), they could not depart the regime, and needed to grow to be much more devoted”, she stated. “I used to be so offended on the system that saved my brothers as hostages.”

In contrast to her dad and mom, Yang rebelled.

She stated she confronted discrimination in Japan – repeatedly denied jobs and fired from a movie challenge due to her Korean heritage.

She additionally needed to grapple with the pro-North Korean sentiment in her neighborhood. Her father was a outstanding determine within the Chongryon organisation – Pyongyang’s de facto embassy in Japan – which ran the college the place she studied literature. Throughout her time on the college, when college students had been requested to interpret texts with chief “Kim Jong Il’s literary theories”, Yang stated she as soon as submitted a clean web page.

“I wished to be free,” Yang stated. “I may have pretended I used to be Japanese, and prevented being sincere about my father and brothers, appearing as if I did not recognise any issues. However to actually break away, I needed to confront all of them.”

After a failed marriage and spending some three years as a instructor at a Pyongyang-linked highschool, she left for New York to review documentary film-making. And it was by films that she started to unpack the story of her household.

Her first documentary, Pricey Pyongyang, was launched in 2005 to vital acclaim, together with on the Sundance and Berlin movie festivals. It provided a uncommon, impartial look inside North Korea, that includes footage from Yang’s camcorder throughout her journeys to go to her brothers.