As she sat in on an all-staff meeting at the restaurant where she worked as a server in Galveston, Texas, Sidney Ramos received a devastating piece of news. On that day in March of 2020, Ramos and her colleagues, like thousands of other food service industry workers employed when the coronavirus pandemic began, were laid off. Her manager said he had no choice but to close, given the health precautions being imposed on businesses at the time.

Ramos, 22, said she immediately began worrying about losing her primary source of income, which she had been using to pay for rent and other expenses while enrolled in college, as well as losing the close relationships she had built with colleagues. But a year later, now that she’s employed in a different industry, Ramos said she remembers her manager’s announcement in a different, more troubling light.

“One thing he said, that I’ll never forget, is that he thought we should be able to risk our lives to serve people during the pandemic,” Ramos recalled in a recent interview. She said this attitude was typical of the service industry, where she had long been encouraged to work long hours while enduring harassment and low wages, even before the pandemic began.

WATCH: Jobs report shows gains, but is it good news for the economy?

“Looking back on it,” Ramos said, “it’s not okay to risk your employees’ lives over someone’s cheeseburger.”

More than a year after COVID-19 triggered one of the most significant global recessions in history, the U.S. economy appears to be recovering, with the Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting 559,000 jobs added last month and a still-high, but lower, unemployment rate of 5.8 percent, less than half of the rate of nearly 15 percent that was reported last summer.

But many Americans going back to work have been deeply changed by the pandemic, and some say the crisis has prompted them to rethink their careers, either by necessity or opportunity. A February Pew Research report found that nearly two-thirds of unemployed Americans had seriously considered changing their occupation or field of work during the pandemic. Another survey conducted this March by Morning Consult on behalf of Prudential found that one in five workers changed their line of work entirely over the past year, and a quarter of workers planned to look for a job with a new employer once the threat of the pandemic had subsided.

After losing her server job, Ramos said she moved to Dallas with her husband to live with his parents and found a job as a nutrition assistant at a local high school. While it’s not the job she envisioned for herself a year ago, she said the switch has been good for her mental health, and she’s thankful the pandemic provided her a way out of the service industry.

“We had a really tough start,” said Ramos, whose husband also lost his job at the beginning of the pandemic. “But In the end, I feel very comfortable with the community I have here at work. I’m treated with respect.”

Two career consultants and an economist said they’ve observed a shift in what Americans are seeking from their work over the past year. “We’ve been through a period of so much stress and uncertainty, and it’s made people really pause and consider what they want their lives to look like as things move back toward normal,” Alison Green, a work advice columnist who runs the blog Ask a Manager, wrote in an email to the PBS NewsHour. Green said she’s received letters from people hoping to find new, more flexible jobs in the same field, or rethinking their careers entirely.

“I do see a shift in the types of employment people are willing to take,” said Matt Weis, chief program officer with the National Able Network, a workforce training program. Weis said their organization advises many people who used to work in the leisure and hospitality sectors — both of which have taken a hit during the pandemic — as well as some who never fully recovered from the last recession and are still seeking full-time jobs.

“What you’re seeing here is a real reckoning of people figuring out what meaningful employment is to them,” he added. While reflecting on their careers during the pandemic, Weis said that some of these job-seekers may be thinking, “I shouldn’t have to take abuse. I shouldn’t have to work three jobs to make a family sustaining wage rates. I should be able to work one job where I can feasibly be relatively happy to go to work each day.”

“I think that there were many low-wage jobs that were lost and many people may not have wanted to have the job before and are now trying to see their options,” said Elise Gould, a senior economist with the Economic Policy Institute who cautioned that while the coronavirus has highlighted just how precarious worker protections can be when it comes to health and child care, she doesn’t expect these conditions to change drastically in a post-pandemic economy unless major policy changes are enacted.

After year of immense change, some workers fear return to ‘normal’

Kate Dahl, a 32-year-old who was living in Washington, D.C., at the beginning of the pandemic, said the crisis made her realize she was no longer happy with her career working in political technology and analytics for Democratic campaigns.

“It’s a pretty millennial crisis,” said Dahl, referring to the common stereotype that her generation is constantly job-hopping. She said she began thinking more about how much she missed her family in Seattle, which she had only been able to visit once a year prior to the pandemic. “I think the pandemic for me just solidified it,” Dahl said of the distance. “When I didn’t have friends or social life, or anything to distract from work … I was deeply unhappy and I made the commitment to move.”

WATCH: How a rise in remote employment may impact post-pandemic work life

Dahl said she was lucky enough to move back in with her parents in the Pacific Northwest after she finished her work on 2020 election campaigns, and began doggedly applying for jobs in the marketing technology space. She said she only received two interviews because she didn’t have many connections in the field, but ultimately ended up landing a role working for a Software as a Service (SaaS) company.

While Dahl said she does miss the “sense of self” she had gained over the years she spent managing teams for political campaigns, overall her work-life balance has improved significantly since leaving that field. “It’s alarming how balanced my life is,” she said. “I’m so used to work being the one and only thing, and this job really recommends and advocates for people to focus on their personal lives.”

Not all Americans were lucky enough to find work as quickly as Dahl. Even the availability of gig work – which can range from app-based services such as Uber, Lyft, and Instacart to contract work and freelancing – mostly declined during the pandemic, despite an uptick in demand for certain services like food delivery, according to The Aspen Institute’s Shelly Steward, who directs their Future of Work initiative. Chris Kirkpatrick, 28, said he had earned an online graduate certificate in data analytics prior to the pandemic, when he was laid off from his job working in youth development. He had been interested in the field of analytics because it seemed more intellectually challenging, and the salaries were higher than the previous field he worked in, but Kirkpatrick said even contract assignments and part-time work had been incredibly competitive to land — the only paid freelance gig he found since losing his job was through a family connection. After applying to nearly 1,000 jobs in the Seattle area with no luck, he said he began looking for remote work outside of the region.

Employees working in other sectors that experienced significant challenges during the pandemic, such as education, said the crisis showed just how ill-equipped their industries were to properly deal with such obstacles.

A photo of John Simms’ empty Albuquerque classroom during the pandemic. Courtesy of Simms.

John Simms, a 7th and 8th grade social studies and history teacher in Albuquerque, said his job was already hard to manage prior to COVID-19 – it wasn’t unusual to work 16 to 20-hour days and still feel like he was behind. “Then you add on top of it the complexities of navigating physical technology and software with almost zero preparation,” he said of the transition to remote learning. Simms described an environment in which he and his fellow teachers were asked to manage all the minutiae of their roles prior to the pandemic, plus more, and it took a serious toll on his mental health.

“I was like, ‘I can’t do this, I’m going to have a nervous breakdown,” Simms recalled. He announced that he would leave his position in April, and is now applying and interviewing for grant-writing positions.

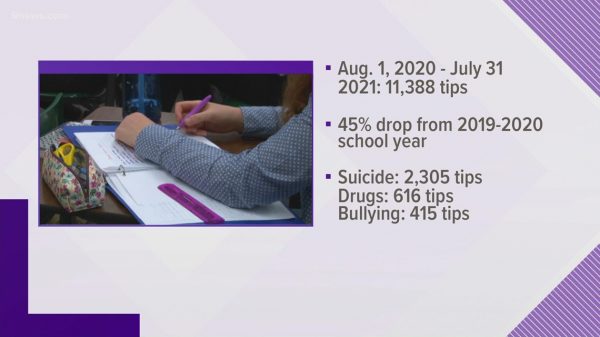

Tyosho Curtis, 46, a school counselor in Columbia, Maryland, said she started having more parents reach out to her about mental health services during the pandemic. She observed that parents of color at her school, in particular, had never seen mental health services as an option. While the events of last year provided a unique entry point for providing this kind of care, she had limited time and resources to devote to all the families who needed, and were asking for, help.

“We talk a lot in schools about making sure that students get the mental health support that they need, but the resources aren’t often there, and a lot of it is just pronouncements and talk,” Curtis said. “What’s the specific action that we take to make sure that mental health services and support get to students and families?” The experience made her think about how she struggled to find a Black therapist for her own daughter, and Curtis began reflecting about how she could address this need for more parents. She’s now looking into going back to school to get certified to work in the mental health care field while continuing her job as a counselor.

“Those of us have been in education for years, we’ve known this forever — we’ve known about the disparities and the gaps, associated with students of color, mental health, and education, but it was definitely exposed. I think there’s a little window we have to be able to really leverage this moment,” she added. “I keep hearing this discussion about going back to ‘normal,’ and my heart clenches. I don’t want to go back to normal, because normal wasn’t okay for a lot of students of color.”

Amid uneven recovery, employers consider how to lure workers back

The economic recovery from the COVID recession has been uneven, with white workers finding employment faster than Black and Hispanic workers, and women in particular falling behind, although female workers did account for more than half of job gains last month. Ten million U.S. mothers with school-age children were not working as of January — an increase of 1.4 million from the previous year, and 705,000 had given up on work outside of the home entirely. As of February, the Economic Policy Institute estimated that 1.1 million older workers had been pushed out of the labor force during the pandemic.

“My big fear here is that people who are already marginalized in the employment world, they’re not going to experience the job recovery close to other other individuals who may have another skill level,” said Weis of the National Able Network.

Sectors such as the service industry have reported difficulties hiring enough workers in recent weeks, but the Economic Policy Institute’s Gould said data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not reflect actual labor shortages because wages in industries such as leisure and hospitality have not gone up significantly. She said it’s likely that employers have had trouble filling jobs due to a variety of different factors keeping Americans from seeking work, including issues with child care and fears about contracting the coronavirus in the office.

As one catering manager, Roberta Montelione, told the PBS NewsHour last month, employers may have to more carefully consider how they treat workers in order to fill jobs as the economy reopens.

“If someone’s raising their hand and saying there’s a labor shortage, my answer is, are you paying them a fair wage? Are you giving them employee health care benefits? Are you taking care of people?” she said. “I think the model is different now. People don’t just show up and work. You need to make sure that you’re invested in them.”

READ MORE: ‘This is not working.’ Parents juggling jobs and child care under COVID-19 see no good solutions

Companies are now considering how to bring back employees to the office, and whether to maintain some option to work from home either on a full or part-time basis. Adopting a more flexible telework policy could have a positive financial impact on both businesses and workers – the firm Global Workplace Analytics estimates that a typical employer can save about $11,000 a year for every person who works remotely half of the time, while employees can save between $640 and $6,400 a year due to reduced costs on transportation and parking, meals and beverages, work clothes and dry cleaning, and so-called “serendipity spending” such as office lunches and football pools with co-workers. But there are also concerns among some economists that so-called “hybrid” work plans could create new inequities among workers, in which young, single men who show up to the office are afforded more opportunities and promotions than women who stay home some days to be with their children, for example.

In another survey of 2,025 full-time workers conducted by Global Workplace Analytics, 77 percent of respondents said that having the option to work from home after COVID-19 would make them happier. The workers that were surveyed ranked health insurance, total compensation and vacation as the most important company benefits, but 23 percent said they would take a pay cut of more than 10 percent to be able to work from home at least some of the time.

Desmond Dickerson, the director of Future of Work Marketing at Microsoft, recently told PBS NewsHour’s economics correspondent Paul Solman that this moment during which many workplaces are considering a major shift provides a good opportunity for employees to ask for more from their employers. “Right now, they do have leverage, after everything that’s happened in the past year, to really push back on the way that they are compensated, the way they’re treated in the workplace, the benefits they’re looking for,” he said. “Everything related to their work is up for negotiation.”

Shelly Steward of the Aspen Institute’s Future of Work initiative said these conversations are happening across employment sectors – not just in corporate spaces. While some Americans may have turned to gig work over the past year because they didn’t have any other options, she said these jobs often pay low wages and do not offer benefits such as health care, highlighting the “importance of a widespread safety net.”

“I think what we’re seeing is more public attention on what workers need – decent pay, added benefits, etc. And these things are tenets of good jobs, whether those jobs are part of the gig economy or not,” Steward said.

Sidney Ramos said that taking a job at her local high school has afforded her the time and wages to be able to start classes at a community college again in the hopes of finishing her Bachelor’s degree. She added that many of the servers she used to work with also found jobs elsewhere during the pandemic, and had similar realizations of feeling they had been expendable in the service industry.

“If you can lose your job at the drop of a hat, why would anyone want to work there?” Ramos said. “I don’t think that’s good for anyone’s mental health to have to go through with that.”