The push for two big infrastructure bills—one bipartisan, the other a much bigger one pushed by Democrats alone—is getting all the attention in Washington right now, and for good reason. Trillions of dollars hang in the balance, as does much of President Biden’s agenda and the question of whether Washington can do anything big in a bipartisan fashion any more.

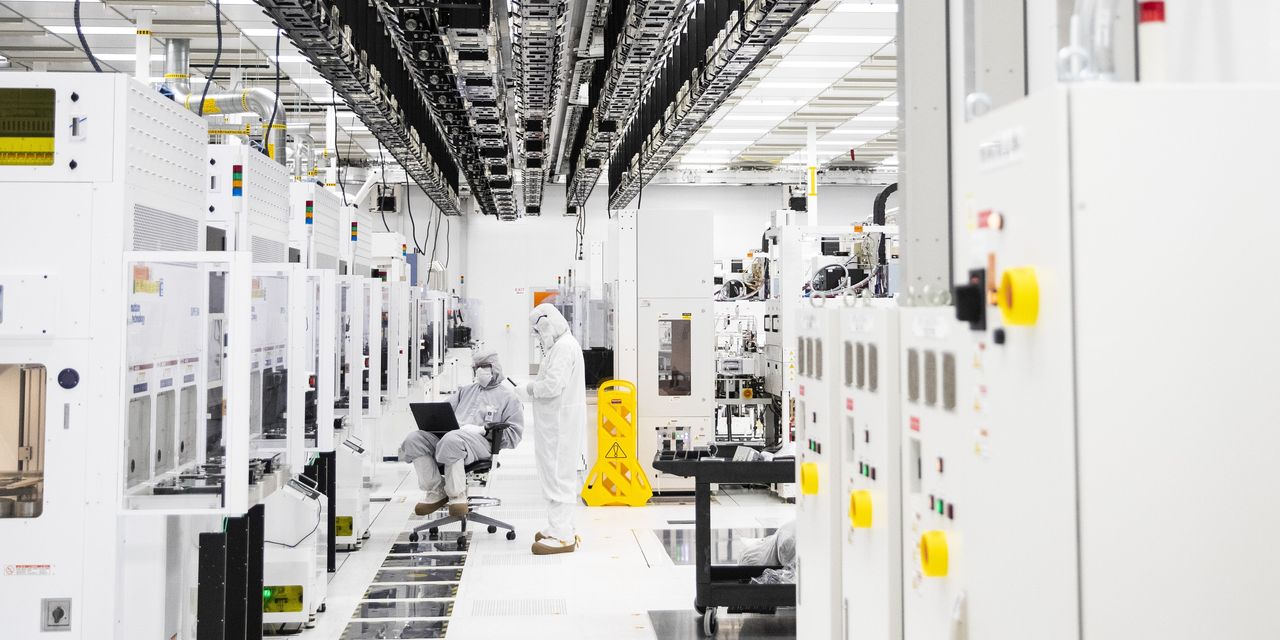

But most people are ignoring a third infrastructure initiative that, while smaller, is freighted with just as much long-term economic and strategic importance. It’s a relatively modest initiative to supercharge America’s at-home production of the semiconductors that now are vital in everyday life. That measure is sitting on a shelf in Washington, awaiting action, while the U.S.’s computer-chip vulnerability grows.

America today is dangerously reliant on foreign producers of semiconductors, crucial components of everything from phones to laptops to cars to smart appliances to much of the equipment in your local hospital. The U.S. share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity has dropped to 12% today from 37% in 1990, according to a study by the Boston Consulting Group.

America’s position has receded while China’s has advanced. Worse, about 40% of the new chip-production capacity projected to be added in the next decade will be in China, which would make it the largest semiconductor manufacturing location in the world.

Already, a shortage of semiconductors is holding up production of cars and driving up prices for consumers. The chief executive of chip manufacturer Intel Corp. told The Wall Street Journal last week that he expects the global shortage will stretch into 2023.