Back in Business is an occasional column that puts the present day in perspective by looking at business history and those who shaped it. Read previous installments of the column here.

Spending with coins or bills shriveled in 2020, with lockdowns isolating millions at home and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging the U.S. public to minimize spread of the virus by making payments “without touching money.”

The pandemic gave the latest push to the decades-long decline of cash and rise of plastic, online and mobile payments.

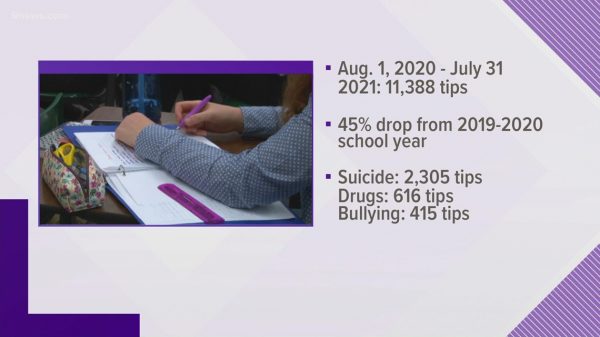

The proportion of consumers who reported using cash for at least one payment monthly dropped to 74.7% last year from 82.4% in 2019, according to a survey of more than 1,900 households nationwide by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Households paid with credit cards 12% more often than they did in 2019, according to the Atlanta Fed; all told, people made 63% of their payments with debit, credit or other payment cards, up from 55% five years earlier.

Let’s face it: Cash is cumbersome, prone to loss and theft, hard to recover and impractical for long-distance transactions. And it can harbor microbes.

Debit and credit cards, and online and mobile payments, are easy, secure and carefree. You can pause your golf game in Kokomo, Ind., to buy something in Kathmandu, Nepal, in the wink of an eye.

Like all good things, however, the convenience of noncash payment has its bad side. It has already made saving harder and spending easier. The dematerialization of money feels good in our daily lives, but it may have long-term consequences we’ve only begun to face.

Mechanical banks, such as this one shown in marketing materials from around 1950, rewarded saving.

Photo:

Buyenlarge/Getty Images

Consider how, in decades past, people saved and spent.

Using piggy banks, which likely originated nearly 1,000 years ago, children put away a penny or a nickel at a time, savoring each clank as coins landed inside.

In the late 19th century, countless parents bought mechanical cast-iron banks for their children. As a little sprout back then, you might have placed a coin in Santa Claus’s hand and laughed as he dropped it down a chimney into the bank’s base—or perhaps you put a coin in an eagle’s mouth and marveled as it leaned down to feed the money to its chicks, who audibly chirped for more.

In the 20th century, your parents might have opened a Christmas Club account for you—or for themselves—at your local bank branch. A regular weekly deposit of a few cents, typically pressed into a colorful cardboard folder, would grow by year’s end into enough money to buy a present for the holidays.

A ‘Trick Pony’ mechanical bank.

Photo:

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

By making money tangible, these savings devices gave it weight and importance—and made deferring gratification feel almost fun.

At the same time, spending money felt like parting with a physical possession. A cashier would “ring you up” at a cash register. As the machine went ka-ching, your purchase literally registered in your ears and mind. As the cashier handed your change back to you, reckoning it to the penny, your money counted—mathematically and metaphorically.

The sum of what you had spent felt even greater than the parts. You felt the pain of paying at the same moment as the pleasure of buying. Spending was tactile and bittersweet.

Cashless payment, on the other hand, has become so easy that it has created a buffer between the pleasure of buying and the pain of paying.

The reward of buying something you want using credit is immediate, just as it is when you shell out cash. But you don’t feel the burden of having to pay for it until later, when your credit-card bill arrives.

Debit cards and other noncash technologies also numb the pain of paying. Not long ago on many highways, you would pull up to a tollbooth, read your ticket, grab a bunch of coins and bills, and hand it all to the toll keeper. You knew you paid $3.95.

Nowadays, zooming through with digital toll technology like E-ZPass, you may have no idea how much you just paid. Once money is dematerialized, using it doesn’t feel like spending.

“As we move away from paying with those gross motor movements,” says Kathleen Vohs, a marketing professor at the University of Minnesota, “we lose that sense of its being an exchange, the gravity of using money.”

Dozens of studies have shown that consumers using credit cards rather than cash are less likely to remember how much they spent, take less time deciding what to buy, are more willing to pay high prices and make a greater number of purchases. They also exert less self-control, buying more junk food, luxury goods and other impulsive items.

Dozens of studies have shown that consumers who use credit cards spend differently than those who pay cash.

Photo:

Isaac Brekken/Getty Images

Studies on debit cards and mobile payments show similar results. A recent neuroscience experiment found that spending with credit cards, rather than cash, activates the same reward centers of the brain that are triggered by cocaine and other addictive drugs. If spending cash hurts, perhaps using credit makes you high.

Of course, it’s hard to say whether people are spending more and saving less because cash is dying—or whether cash is dying because people are spending more and saving less.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, Americans saved roughly 10% of their disposable personal income. In the late 1980s, U.S. consumers began to save less until, by 1995, they saved only 3% of available earnings. That number rebounded in the 2000s and 2010s, then shot up during the pandemic as the economy locked down and people received government stimulus payments.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

If you’ve been using cash less often lately, how have your spending or saving habits changed? Join the conversation below.

One of the main factors driving the long-term decline of savings in the U.S. is the fall in interest rates since the early 1980s, says Jonathan Parker, a financial economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Lower interest rates reduce the return on bank accounts, cut the cost of borrowing, and raise the value of stocks and real estate, making people feel they can spend more.

Yet cash still seems to provide a comfort and peace of mind other forms of payment don’t. During the pandemic, people hoarded cash; holdings shot to an average of $533 per household in August 2020 from $257 in October 2019, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. (The rise is significant even considering stimulus payments during the period.)

Finally, consider that the leading cryptocurrency is called bitcoin, not bitmoney. Although it exists in digital form, bitcoin is commonly visualized as a gold-colored metal disc emblazoned with a B and two vertical stripes, much like a dollar sign.

Many owners of bitcoin say they are “hodling,” often interpreted to mean “holding on for dear life.”

It’s almost as if they crave something tangible to replace what we have lost.

In his regular Intelligent Investor column, Jason Zweig writes about trends in the investing world, portfolio strategy and financial decision-making. Sign up for his newsletter here.

Write to Jason Zweig at intelligentinvestor@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8